An overview of the current state of collection of biometric information, the opportunities it presents and potential problems that could arise from growing databases of records, including how immigrant communities, such as in the US, can be affected by the way data is collected, stored, and shared

by Jennifer Lynch, Electronic Frontier Foundation

The collection of biometrics—such as fingerprints, DNA, and face recognition-ready photographs—is becoming more and more a part of the society in which we live, no less so for immigrants within the United States. State and local law-enforcement agencies are quickly adopting mobile biometrics scanners like the fingerprint scanners in use by the LAPD,5 though many of the newer scanners, like the ‘MORIS’ (Mobile Offender Recognition and Information System), are able to collect and identify much more than fingerprints including iris prints and face images taken from several inches to several feet away.

The collection of biometrics—such as fingerprints, DNA, and face recognition-ready photographs—is becoming more and more a part of the society in which we live, no less so for immigrants within the United States. State and local law-enforcement agencies are quickly adopting mobile biometrics scanners like the fingerprint scanners in use by the LAPD,5 though many of the newer scanners, like the ‘MORIS’ (Mobile Offender Recognition and Information System), are able to collect and identify much more than fingerprints including iris prints and face images taken from several inches to several feet away.

Both the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) are in the process of expanding their biometrics databases to collect much more information, including face prints and iris scans. As of January 2012, the FBI has been working with several states to collect face recognition-ready photographs of all suspects arrested and booked. Once these federal biometrics systems are fully deployed, and once each of their approximately 100+ million records also includes photographs, it may become trivially easy to find and track people within the United States.

Undocumented people living within the United States, as well as immigrant communities more broadly, are facing these issues more immediately than the rest of society and are uniquely affected by the expansion of biometrics collection programs. Under DHS’s Secure Communities program, states are required to share their fingerprint data—via the FBI—with DHS, thus subjecting undocumented and even documented8 immigrants in the United States to heightened fears of deportation should they have any interaction with law enforcement. Further, under data-sharing agreements between the United States and other nations, refugees’ biometric data may end up in the hands of the same repressive government they fled. Should they ever be deported or repatriated, they could face heightened risks from discrimination or even ethnic cleansing within their former home countries.

Devices and tools

There are many ways to collect biometrics, though each falls into one of three general categories: 1) invasive, such as a blood sample, taken to collect a person’s DNA; 2) minimally or non-invasive, such as a fingerprint or iris scan; or 3) collected without the subject’s knowledge, such as photographs taken from a distance or DNA collected from discarded biological material. Each of these has different implications for privacy.

Minimally or non-invasive though known biometrics collection is most common. Most people living in the United States, including immigrants, have provided a biometric to a state or federal government agency through some minimally or non-invasive collection program. DHS collects approximately 300,000 fingerprints per day from non-U.S. citizens crossing the U.S. borders, and the State Department uses biometric identifiers in visas and other travel documents. Anyone arrested and booked for a crime will be required to provide fingerprints, and many people who apply for a driver’s license will provide face-recognition ready photographs. And anyone who applies for employment with the federal government or for a sensitive position requiring a background check (such as working for law enforcement or with the elderly or young children) will be asked to supply a fingerprint.

Biometrics collection tools are getting smaller, more advanced, and less obtrusive, increasing their use for non-invasive though known, as well as unobtrusive, collection purposes. Increasingly, devices are portable, transmit data wirelessly, and are designed to allow collection, verification, and identification “in the field.” Many now include cameras, or like the MORIS (Mobile Offender Recognition and Information System), work with devices in general use, such as the iPhone, to capture face-recognition ready photographs. This means law enforcement can carry biometrics collection tools with them in the field and can easily identify people on the fly.

Recent advances in camera and surveillance technology have improved the accuracy of biometrics capture and identification at a distance, making unobtrusive biometrics collection easier. These technologies, incorporated into private and public security cameras and other cameras already in use by police, are more capable of capturing the details and facial features necessary to support facial recognition-based searches. They can record high-quality photographs and video and store it for a long time.

Mobile biometrics scanners may connect to local, regional, statewide, or federal biometrics databases (or all four), or may connect to a database run by a private company under contract with the local law-enforcement agency. Since September 2010, the FBI’s mobile fingerprint scanners also communicate with and search against IDENT, the DHS biometric database, to facilitate data sharing under the Secure Communities program.

Collection and storage

Biometrics can be stored in several ways, but in general, biometrics systems do not store the actual image of the biometric. Instead, they analyze the biometric to create a digital “template” (a mathematical representation) from it, which is made up of 1s and 0s. This template may then be stored in a database or on the scanning device itself to be used for matching and verification. The agency that collected the biometric may then chose to maintain it in its original form.

Many different biometrics databases exist in the United States, but most are similar in that they combine a single biometric—generally a fingerprint—with a subject’s biographical data, such as name, address, social security number, telephone number, e-mail address, booking and/or border crossing photos, gender, race, date of birth, immigration status, length of time in the United States, and unique identifying numbers (such as a driver’s license number). The two largest biometrics databases in the world—and the two most likely to hold immigrants’ data—are the FBI’s Integrated Automated Fingerprint System (IAFIS) and DHS’s Automated Biometric Identification System (IDENT), a part of its U.S. Visitor and Immigration Status Indicator Technology (US-VISIT) program. Each database holds 100+ million records.

IAFIS’s criminal file stores fingerprints taken from people arrested at the local, state, and federal level and also accepts latent prints taken from crime scenes. IAFIS’s civil file stores fingerprints taken as part of a background check for many types of jobs, such as childcare workers, law-enforcement officers, lawyers, and federal employees. IAFIS includes over 71 million subjects in the criminal master file and more than 33 million civil fingerprints. IAFIS supports over 18,000 law-enforcement agencies at the state, local, tribal, federal, and international level.

IDENT stores biometric and biographical data for individuals who interact with the various agencies under the DHS umbrella, including Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), Customs and Border Protection (CBP), the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), the U.S. Coast Guard, and others. Through US-VISIT, DHS collects fingerprints from all international travelers to the United States who do not hold U.S. passports.23 USCIS also collects fingerprints from citizenship applicants and all individuals seeking to study, live, or work in the United States through its two main programs, Refugees, Asylum and Parole Services (RAPS) and the Asylum Pre-Screening System (APSS). And the State Department transmits fingerprints to IDENT from all visa applicants. IDENT processes more than 300,000 ‘encounters’ every day and has 130 million fingerprint records on file.

In addition to the federal databases, each of the states has its own biometrics databases—generally a fingerprint database and a DNA database and some regions like Los Angeles also have regional databases. The prints entered into these databases are shared with the FBI, and under the Secure Communities program, FBI shares these prints with DHS to check a person’s immigration status.

Interoperability and data sharing

Before September 11, 2001, the federal government had many policies and practices in place to silo data and information within each agency. Since that time the government has enacted several measures that allow—and in many cases require—information sharing within and among federal intelligence and federal, state, and local law-enforcement agencies. For example, currently the FBI, DHS, and Department of Defense’s biometrics databases are interoperable, which means the systems can easily share and exchange data.54 This has allowed information sharing between FBI and DHS under ICE’s Secure Communities program.

Similarly, DHS is now sharing its data on asylum applicants more broadly with non-DHS agencies, per federal regulation 8 CFR §208.6(a). According to a June 30, 2011, Privacy Impact Assessment, DHS now shares the entire Refugees, Asylum and Parole Services (RAPS) database with the National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC), a division of the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, under a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU). And states are sharing biometric data with the federal government as well. In addition to sharing criminal fingerprint and DNA profile data with the FBI, states are sharing fingerprints indirectly with DHS through Secure Communities. And some states are also sharing DMV face-recognition data with the FBI on an ad hoc basis.

Corporate and foreign sharing

The collection of biometric and biographic data is not limited to federal, state, and local governments. Private companies and foreign governments also collect extensive amounts of biometric data. Because many private and foreign biometrics systems are linked to or accessible by government systems and employees, and because immigrant data are caught up in these systems, they could have a significant impact on privacy and immigrant communities.

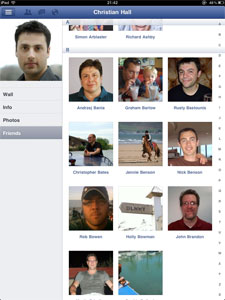

One of the best-known private biometrics databases is maintained by Facebook. Facebook’s face recognition service allows users to find and tag their friends, and due to the high number of photos uploaded to and tagged on Facebook, the service has seen dramatic increases in accuracy over the last several years. Facebook currently has over 845 million monthly active users, and requires each of those users to sign up under their real names. Facebook then makes its users’ names and primary photos public by default. The government regularly mines this data to verify citizenship applications, for evidence in criminal cases, and to look for threats to U.S. safety and security. It is likely the government will try to find a way to take advantage of Facebook’s face recognition service for each of these purposes soon.

One of the best-known private biometrics databases is maintained by Facebook. Facebook’s face recognition service allows users to find and tag their friends, and due to the high number of photos uploaded to and tagged on Facebook, the service has seen dramatic increases in accuracy over the last several years. Facebook currently has over 845 million monthly active users, and requires each of those users to sign up under their real names. Facebook then makes its users’ names and primary photos public by default. The government regularly mines this data to verify citizenship applications, for evidence in criminal cases, and to look for threats to U.S. safety and security. It is likely the government will try to find a way to take advantage of Facebook’s face recognition service for each of these purposes soon.

The federal government does not appear to have formal data-sharing arrangements with private companies that collect biometrics, but it does have such arrangements with foreign governments. The FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Service (CJIS) division has information-sharing relationships with 77 countries. Also, ICE and the FBI have a draft agreement allowing them to share information on deportees with the countries to which they are deported, and DHS has entered into agreements with foreign governments to provide such information on deportees upon repatriation.72 This kind of biometrics sharing could prove disastrous for repatriated refugees or immigrants from countries with a history of ethnic cleansing.

Proposals for change

The over-collection of biometrics has become a real concern, especially for immigrants and immigrant communities in the United States, but there are still opportunities—both technological and legal—to prevent the problem from getting worse.

Given the uncertainty of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence in the context of biometrics and the fact that biometrics capabilities are currently undergoing ‘dramatic technological change,’ legislative action could be a good solution to curb the over-collection and over-use of biometrics in society today and in the future.

If legislation or regulations are proposed in the biometrics context, the following principles should be considered to protect privacy and security. These principles are based in part on key provisions of the Wiretap Act and in part on the Fair Information Practice Principles (FIPPs), an internationally recognized set of privacy protecting principles.

Limit collection

The collection of biometrics should be limited to the minimum necessary to achieve the government’s stated purpose. For example, collecting more than one biometric from a given person is unnecessary in many situations. Similarly, the government’s acquisition of biometrics from sources other than the individual to populate a database should be limited. For example, the government should not obtain biometrics en masse to populate its criminal databases from sources such as state DMV records, where the biometric was originally acquired for a non-criminal purpose, or from crowd photos.

Define clear rules

Each type of biometric should be subject to clear rules on when it may be collected and which specific legal process—such as a court order or a warrant is required prior to collection. Collection and retention should be specifically disallowed without legal process unless the collection falls under a few very limited and defined exceptions. For example, clear rules should be defined to govern when law enforcement or similar agencies may collect “abandoned” biometrics such as DNA, or biometrics revealed to the public, such as a face print.

Each type of biometric should be subject to clear rules on when it may be collected and which specific legal process—such as a court order or a warrant is required prior to collection. Collection and retention should be specifically disallowed without legal process unless the collection falls under a few very limited and defined exceptions. For example, clear rules should be defined to govern when law enforcement or similar agencies may collect “abandoned” biometrics such as DNA, or biometrics revealed to the public, such as a face print.

Limit data storage

For biometrics such as DNA that can reveal much more information about a person than his or her identity, rules should be set to limit the amount of data stored. For example, if DNA must be collected for identification purposes, the sample should be destroyed immediately after the profile is extracted and entered into the database. Similarly, techniques should be employed to avoid over-collection of biometrics such as face prints (such as from security cameras or crowd photos) by, for example, scrubbing the images of faces that are not central to an investigation.

Limit combinations

Different biometric data sources should be stored in separate databases. If biometrics need to be combined, that should happen on an ephemeral basis for a particular investigation. Similarly, biometric data should not be stored together with non-biometric contextual data that would increase the scope of a privacy invasion or the harm that would result if a data breach occurred. For example, combining facial recognition technology from public cameras with license plate information increases the potential for tracking and surveillance. This should be avoided or limited to specific individual investigations.

Limit retention

Retention periods should be defined by statute and should be limited to no longer than necessary to achieve the goals of the program. Data that is deemed to be “safe” from a privacy perspective today could become highly identifying tomorrow. For example, a data set that includes crowd images could become much more identifying as technology improves. Similarly, data that was separate and siloed or unjoinable today might be easily joinable tomorrow. For this reason retention should be limited, and there should be clear and simple methods for a person to request removal of his or her biometric from the system if, for example, the person has been acquitted or is no longer under investigation.117

Define use and sharing

Biometrics collected for one purpose should not be used for another purpose. For example, biometrics such as fingerprints collected for use in a criminal context should not automatically be used or shared with an agency to identify a person in an immigration context. Similarly, photos taken in a non-criminal context, such as for a driver’s license, should not be shared with law enforcement without proper legal process.

Enact robust security

Because biometrics are immutable, data compromise is especially problematic. Using traditional security procedures, such as basic access controls that require strong passwords and exclude unauthorized users, as well as encrypting data transmitted throughout the system, is paramount. However security procedures specific to biometrics should also be enacted to protect the data. For example, data should be anonymized or stored separate from personal biographical information. Strategies should also be employed at the outset to counter data compromise after the fact and to prevent digital copies of biometrics. For example, biometric encryption118 or “hashing” protocols that introduce controllable distortions into the biometric before matching can reduce the risk of data compromise. The distortion parameters can easily be changed to make it technically difficult to recover the original privacy-sensitive data from the distorted data, should the data ever be compromised.

Mandate notice procedures

Because of the real risk that people’s biometrics will be collected without their knowledge, biometrics rules should define clear notice requirements to alert people to the fact that their biometrics have been collected. The notice provision should also make clear how long the biometric will be stored and how to request its removal from the database.

Standardize accountability

All database transactions, including biometric input, access to and searches of the system, data transmission, etc. should be logged and recorded in a way that assures accountability. Privacy and security impact assessments, including independent certification of device design and accuracy, should be conducted regularly.

Ensure independent oversight

Every entity that collects or uses biometrics must be subject to meaningful oversight from an independent entity, and individuals whose biometrics are compromised should have a strong and meaningful private right of action.

Biometrics collection and its accompanying privacy concerns are not going away. Given this, it is imperative that government acts now. This is important not just for immigrants and immigrant communities, but also for democratic society as a whole.