An exploration into the emergence of a phenomenon that is being hailed as ‘the second revolution’ in terms of mobility management in urban and suburban transport, using the capabilities of smart phones and telecoms to provide a global management of various forms of mobility – public as well as individual

by Etienne Graindor, Belgian Mobility Card

Urban and suburban public transport providers are seeing a period confirming that they are once again becoming attractive. Many reasons may be evoked to explain this ‘return’ to public transport that are now clearly not just more only devoted to ‘captive’ customers but appear to be a valuable alternative for individual mobility.

Urban and suburban public transport providers are seeing a period confirming that they are once again becoming attractive. Many reasons may be evoked to explain this ‘return’ to public transport that are now clearly not just more only devoted to ‘captive’ customers but appear to be a valuable alternative for individual mobility.

The main reason is certainly the congestion in cities – and not only the city centre areas, which make the use of individual transport almost impossible; the circulation surfaces being constant, the densification both of office areas and housing (certainly those dating from the first half of the 20th century when no garage space was included in the buildings) have created the basis of local traffic congestion, completed by the drastically increased demand originating from the suburbs.

If the initial consequence of this phenomenon, which began during the sixties, was to ‘citify’ some areas in the town centre (all inhabitants disappearing in favour of just office buildings), it also pushed populations out to the suburbs in an ‘all car attitude’ that, for example, translated into the creation of shopping centres offering numerous parking spaces. One or two decades later, a similar centrifugal phenomenon could be also observed in the tertiary sector, introducing a new pattern to the cities quite different to the previous radio-concentric one and once again thought more suited to individual transport.

The first revolution

From the sixties onwards and in order to save the city centres, the strategic answer of the town planners was to improve the quality of the public transport offered by creating new segregated infrastructures, mainly tunnels or elevated routes, to avoid any effect of the congestion on the quality of public transport (greater commercial speed and regularity). Many underground systems appeared at that time and networks were redesigned; numerous surface trunk routes were converted to feeder lines to the new top level system, whoever the operator.

Consequently and to complete the efficiency of this new PT pattern, an initial revolution has been introduced in the commercial approach by the marketing of integrated fares, mainly season tickets. Historic rules inherited from the ‘private’ transport companies were abandoned and the various networks now form one unique transport system. To cope with this new situation, ticketing systems have been adapted and evolve – not yet everywhere but on a large scale – to magnetic strip ticketing.

Smart ticketing

The proven weakness of magnetic systems and the maintenance costs of equipment containing mechanical parts led to another development, begun in the nineties: ‘smart ticketing systems’ based on contactless cards simplifying the various equipment (e.g. automatic sale, validators, desk devices) and accelerating passenger flow. Furthermore, the validation requirement introduced for social control (one must prove ownership of a valid transport contract) was also considered as a means to provide references for sharing the revenues between the transport companies operating the ‘integrated transport system’.

One can observe some developments from the introduction of the smart ticketing:

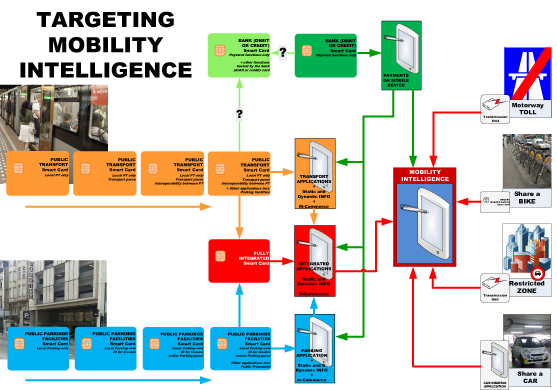

- for public transport, the integration of non-transport contracts generally called “multi-application” (e.g. events, socio-cultural activities), the consideration of other forms of mobility (car or bike sharing), the card being used only as an identifier, and some forms of inter-operability (e.g. the possibility of loading local transport contracts on non-locally issued media or to accept cross-frontier contracts);

- for parking facilities, for which the switch from magnetic stripe tickets to smart ticketing is more recent, the introduction of multi car park accessibility with original commercial offers (both for private parking spaces as well as for on-street parking) ;

- finally, the integration of both kind of contracts (public transport and car park facilities) on one unique smart card creates “integrated mobility media”.

Note: This recent development may include means of payment, mainly issued from the transport applications themselves, as up to now the bank or credit cards industries have proven to keep distances with the possibility of integrating transport/parking functions with their bank/credit functions.

As mobile telephones penetrate the individual communications market, transport operators are developing information applications both for static and dynamic (real time) information. However, due to technological limitations this initially excludes any form of ticketing except occasionally “sms tickets” … essentially profitable for telecom operators.

When NFC (Near Field Communication) mobile phones became available on the market, new concepts could be introduced as this kind of mobile device is, due to the antenna on the back of the device, acting as a smart card. The real added value of NFC mobile phones relates to the capability of such individual equipment to integrate ticketing, static and dynamic information and sales functions (the NFC mobile phone is an individual vending machine, for which investment is transferred to the customer.) NFC telephones may also be used with other kinds of application, such as the right to access to restricted central zones, motorway tolls or bike or car sharing.

The second revolution

Some new sociological trends are now observed and strongly influence the modal split between public and private transport modes:

- increase of single-parent households, even with children, in relation to the increase of divorces;

- ‘just married’ couples’ preference for urban residence, even in smaller areas, in relation to the present economic situation;

- ownership of an individual means of transport considered less and less as personal valorization.

Furthermore, traffic congestion reached such levels that regulation of access to central zones needs to be introduced, as well as price regulation for the use of some infrastructures for road traffic (toll for motorways or specific civil works). In parallel, not owning a car does not mean that the populations concerned do not use individual means of transport. To satisfy this new demand, new concepts of bike or car sharing are now marketed, sometimes with elaborate management systems based on the new generation of smart phones.

The coming months will therefore see the emergence of a second revolution in terms of mobility management, using the capabilities of smart phones and telecoms to provide a global management of various form of mobility, public as well as individual. This may be called ‘Mobility Intelligence’ and will cover:

- static and dynamic information both for individual and public transport, including availability of the shared means of transport or for parking capacity around the PT line stations;

- assistance in deciding the most efficient mix of transport modes for a particular demand at one specific date and time;

- eventual booking for some components of this specific demand (e.g.shared car reservation or parking reservation at destination);

- pricing for those different parts of the mobility;

- payment if not covered by seasonal contracts;

- potential complementary contracts for social or cultural activities (e.g. accessibility to events or cultural season contracts) acquired through m-commerce and loaded for use in the mobile system.

Developing this mobility intelligence has already started for some pilots and will certainly be a fascinating challenge for the near future.