A study on the issues of safer cities and how urban leaders can draw community support for surveillance programs

by AGT International

Hundreds of new cities will emerge over the next 15 to 20 years, while most of those already in existence will continue to grow at a rapid pace. At one extreme there might be a city in chaos, where crime goes unchecked and criminals have little fear of being apprehended. At the other extreme we might find a city that operates like the proverbial ‘police state’, following innocent people’s every move, monitoring all conversations and actions, and invading the privacy of every resident and visitor in the name of keeping them safe.

Hundreds of new cities will emerge over the next 15 to 20 years, while most of those already in existence will continue to grow at a rapid pace. At one extreme there might be a city in chaos, where crime goes unchecked and criminals have little fear of being apprehended. At the other extreme we might find a city that operates like the proverbial ‘police state’, following innocent people’s every move, monitoring all conversations and actions, and invading the privacy of every resident and visitor in the name of keeping them safe.

Somewhere between these two extremes lies the ideal safe city. But what does that ‘ideal’ look like? For some, the presence of video surveillance cameras in public spaces is perfectly acceptable. For others, concerns over personal privacy weigh heavily and the use of surveillance leaves them feeling invaded and even concerned about the possibility of being unduly accused of wrongdoing. So how can city leaders draw support for new or existing surveillance programs?

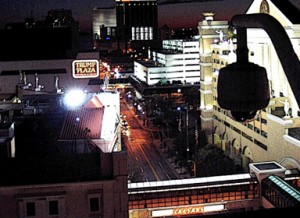

City surveillance

Given the complexity of modern urban environments, advanced analytic CCTV and other modern surveillance innovations (such as the automated systems that analyze and interpret the information such cameras capture) represent the most effective and efficient way to protect the cities of today and tomorrow. That said, municipal leaders must also determine how best to gain public support for their cities’ surveillance programs. Failure to do so can be expensive: for example, in some cities, public backlash to what was perceived as excessive surveillance and an invasion of privacy has resulted in the need to uninstall cameras. Granted, there are parts of the world where personal privacy is not a governmental consideration. But, even in such cases, citizens have been known to rise up or organize demonstrations in protest of a real or perceived disregard for individuals’ privacy concerns.

The bottom line is that city leaders have several competing but interrelated responsibilities. They must ensure people’s safety and achieve a thriving business environment while remaining respectful of residents’ privacy and vigilant against potential abuses of the surveillance program being implemented.

Education

For many, the term “CCTV” evokes images of clunky, independently functioning security cameras that capture footage to be viewed only after a criminal event has taken place. While this notion of “CCTV as witness” may have been accurate ten years ago, today it is far outdated. CCTV has evolved both technologically and operationally, and it is critical that city residents and business owners know the facts— those favorable and not— about the current generation of video surveillance tools.

Though helpful for evidence gathering, first-generation CCTV relied too heavily on human operators who, being human, came to the table with biases, as well as limited amounts of concentration, bandwidth and situational awareness. It was largely these limitations that gave rise to concerns about the efficacy of the technology and the ethics behind the use of surveillance in the first place. Today’s Advanced Analytic CCTV is primarily differentiated by its ability to reason—to learn what unusual or illegal behavior looks (and sounds) like, pinpoint suspicious activities amidst a vast background of lawful goings-on, and communicate with human operators in real time—giving police and other first-responders an opportunity to make decisions and act before events unfold. Yes, Advanced Analytic CCTV offers the potential to not only solve crimes, but to prevent and in some cases predict them.

Advanced analytic CCTV

Advanced Analytic CCTV helps authorities to literally see the bigger picture. Imagine a situation where a vehicle that is being driven erratically is simultaneously matched against black lists of stolen and suspected vehicles, and continuously tracked across a wide geographic area by ‘smart’ cameras that collaborate with each other as well as sensors in order to more fully monitor the situation. When plugged into a mobile or central command and control center, footage could then be automatically combined and synthesized with a range of other video, audio, and cellular data to enable real-time analysis that draws inferences and triggers alerts as to whether that particular car is, indeed, likely to pose a threat to public safety. Light years beyond first-generation cameras, Advanced Analytic CCTV’s realtime, multi-source, algorithmic approach to data analysis and interpretation may help to overcome some of the potential arguments against CCTV, but only if citizens are made aware of the technology’s primary advantages: Advanced Analytic CCTV’s use of multiple data sources provides a more complete picture that reduces false-positive alerts.

Advanced Analytic CCTV helps authorities to literally see the bigger picture. Imagine a situation where a vehicle that is being driven erratically is simultaneously matched against black lists of stolen and suspected vehicles, and continuously tracked across a wide geographic area by ‘smart’ cameras that collaborate with each other as well as sensors in order to more fully monitor the situation. When plugged into a mobile or central command and control center, footage could then be automatically combined and synthesized with a range of other video, audio, and cellular data to enable real-time analysis that draws inferences and triggers alerts as to whether that particular car is, indeed, likely to pose a threat to public safety. Light years beyond first-generation cameras, Advanced Analytic CCTV’s realtime, multi-source, algorithmic approach to data analysis and interpretation may help to overcome some of the potential arguments against CCTV, but only if citizens are made aware of the technology’s primary advantages: Advanced Analytic CCTV’s use of multiple data sources provides a more complete picture that reduces false-positive alerts.

In addition, it conducts automatic impartial analyses of captured information, removing the subjective and potentially biased human element. That said, surveillance is still surveillance, and having one’s everyday activities looked at—even if only by qualified operators— is not for everyone. But not everyone is inherently opposed to surveillance. Teens and young adults (college students in particular), for example, are often more open to public surveillance than other groups. Raised with Facebook and Twitter rather than George Orwell, many ‘Millennials’ are often guilty of ignoring their personal privacy, tagging photos of one another on social networking sites, and even geotagging themselves as they move about. High school and college campuses are often covered with surveillance cameras; and reality-television shows, such as ‘Big Brother’, have helped to make surveillance an accepted part of popular culture.

Rather than balking at surveillance devices, today’s young people often respond to the idea of being watched by watching back, using smart phones to capture and share photos and videos of anything they find interesting or objectionable on the part of public safety or school officials.

In determining the surveillance program’s apparent success, stakeholders in the city of Baltimore repeatedly emphasized the importance of community input through the convening of open public meetings, the invitation of public comment, and the clear explication of the rationale behind camera placement decisions.

Buy-in for the operation of Advanced Analytic CCTV and other surveillance depends on people’s confidence that they understand the proposed solution and have the option to contribute to program success. The following is a suggested phased approach for building community education and engagement into a city’s surveillance program. The following guidelines provide a foundation to get communities involved in and more accepting of their cities’ surveillance programs.

Phase 1: new or expanded surveillance

Community engagement should start at the beginning, when surveillance technologies are first being considered for a particular neighborhood. Doing so establishes trust and confidence, as members of the community feel regarded and respected for their input and opinions. Town hall meetings, surveys, and special gatherings with community leaders should be used to gather opinions regarding the necessity of surveillance and provide details on the city’s implementation plan.

It is during this phase that law enforcement first has the opportunity to educate the community on how surveillance technologies work and how they work with other policing strategies, making the public aware that surveillance is only one element of police efforts and not the entire solution.

This can be accomplished through policing demonstrations offered during publicly held meetings or on the Internet. This is an effective way to get the public to understand that surveillance technologies have their place, but are not intended to push out other policing efforts.

Phase 2: planning

Once implementation is agreed upon, the community should be involved in developing a plan.

More specifically, the public should be consulted about the proposed areas to be monitored; the number of cameras to be deployed and their locations; realistic expectations for the program’s success; what crimes are expected / not expected to be discouraged; the planned program duration and evaluation period; costs, including installation, maintenance, and operation of the system, as well as necessary construction/ demolition in order to accommodate installation; plans for funding the program; and ways in which suggestions and complaints can be submitted. It should also be noted that while allaying concerns for personal privacy is a major driver behind efforts to involve the community in this phase of the process, the community itself can also be a uniquely qualified source of information: citizens and businesses often know best where to place cameras for maximum effectiveness and for this reason alone, they should be listened to.

Phase 3: implementation

The community should be consulted on any post-launch changes to the surveillance strategy, including the addition, subtraction, or relocation of cameras and the reasons for those changes, as well as changes to the coverage area or the intended use of captured content. It is during the implementation phase that police can demonstrate to the public that cameras cover only public spaces and do not venture into private property and/or people’s homes.

Once cameras are turned on, city leaders can use the technology itself to deliver transparency, efficiency, and accountability. Affording citizens and business owners the ability to see live CCTV camera footage, for example, accomplishes two things: it reduces the ‘us’ vs. ‘them’ mentality due to the fact that average citizens can see and interpret information in the same way as police do; it can also provide a system of checks and balances for police who might otherwise misuse cameras to profile or track individuals based solely on their physical appearance or unseemly (albeit legal) behavior.

Phase 4: evaluation

Cities should include the community in regular evaluations of their surveillance programs. Such evaluations should address outcomes, such as whether the program has met key performance indicators (e.g., reduced crime; faster arrests and prosecution of criminals) and where the program is succeeding and failing and why. Again, it is the communities that can often best answer these questions and provide meaningful input for future improvements. For this reason, evaluation should rely heavily on community surveys as well as official statistics and metrics. In the evaluation phase, public officials should make every effort to publicly demonstrate reduced crime rates, increased conviction rates, lowered court costs and other wins, while not being afraid to acknowledge failures, such as crime displacement (i.e., crime moving from one area to another) or diffusion (i.e., different types of crime replacing those that were reduced as a result of surveillance).

Technologies

When public surveillance technologies such as Advanced Analytic CCTV are strategically implemented, they can help to prevent and solve crime and instill societal improvements in a number of ways:

- potential offenders might abstain from criminal activity if they know they are being monitored

- cameras can increase the perception of safety, leading the average citizen to more frequently venture into public spaces; more people on the street typically results in fewer incidents of crime

- police can be alerted to crimes and potentially dangerous situations before they occur, giving them more information and time to determine and execute an appropriate response

- video footage documenting criminal activity and identifying perpetrators and witnesses might aid in investigations and prosecutions, ultimately preventing future crimes.